During my studies of Samuel Beckett and The Theatre of the Absurd this year, I couldn’t help but make comparisons to a concert film I saw over the summer and which really ingrained itself into my brain. The Jonathan Demme directed Talking Heads Concert film Stop Making Sense. I wondered if anybody had ever written anything on the stage direction heavy and seemingly nonsensical plays of Beckett such as Waiting for Godot and Endgame and the theatrically sublime performance art piece that is Stop Making Sense.

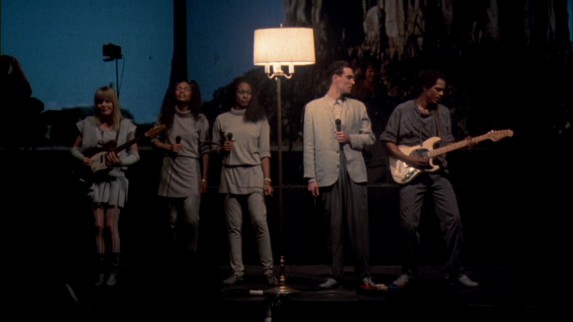

I am to understand that the intent of Beckett’s work is to evoke, subvert and question the mimetic medium of the stage which is why I wonder if perhaps Stop Making Sense is, in it own way, trying to do something similar through a rock concert. Much like a theatre play, Stop Making Sense relies heavily upon stage lighting, blocking, exaggerated performance and movements as well as a narrative sequence of unfolding shifts and changes in the band’s dynamic. There are props (most notably a lamp and a pair of reading glasses) and even subtle costume and hair style changes from Byrne. But the comparison to Becket, for me, is Byrne himself and his seemingly intentional decision to never leave the stage. A class troupe of Beckett’s drama and raison d’etre.

The importance of movement and performance through both Byrne and Beckett cannot be underestimated. Where Byrne follows his own rhythm, we see a separation between performer and performance. Trying to rationalise Byrne’s movements throughout Stop Making Sense misses the absurdist and also highly spiritual intent of why he acts the way he does. The title itself is a statement as to why bother trying to find logic, it doesn’t mean anything. Byrne asserts this point when asked about the title, stating, “It’s good advice. because music and performing does not make sense.” going on to state that, “… music is very physical and often the body understands it before the head.” (Byrne 1984) In this way, Byrne’s music becomes persona through his medium. His music encapsulates a spirit in which Byrne himself becomes a play thing to the music and rhythms he hears. The theatricality of his motions harper back to Beckett’s own use of characters as marionettes playing out in his naturalistic vision. In Stop Making Sense, naturalism seems to blend with surrealism as we see depictions of Byrne dancing with a tall lamp during “This Must Be The Place”, Incorporating a cross between sign language, epilepsy and tribal ritual hand gestures in “Once In a Lifetime” and “Life During Wartime” and falling from his wounds as the victim of “Psycho Killer”.

Beckett’s characters on the other hand portray a more rigid and metered performance. They are not given that same absurdist carelessness of expression but instead find the madness and obsessive compulsive ticks in a world which may not exist anymore or may not even abide by the moralities its characters still harbour. The introduction of Endgame for example exemplifies this staccato of movement to an almost ironically comic effect. Or even the hat switching moment in Waiting for Godot. Played in this way to avoid the memetic convention of realism through repetition.

“He looks up at window left. He turns ad looks at window right. He goes and stands under window right. He looks up at window right. turns and looks at window left. he goes out, comes back immediately with a small step-ladder, carries it over and sets it down under window left, gets up on it, draws back curtains,. He gets down, takes six steps [for example] towards window right, goes back for ladder, carries it over and sets it down under window right, gets up on it draws back curtain. he gets down, takes three steps towards window left goes back for ladder, carries it over and sets it down under window left, gets up on it., looks out window. Brief laugh.” (Beckett, Endgame 5)

One of the most striking similarities between Byrne and Beckett also come from their writings. Byrne’s song “Once in A Lifetime” seems an adequate tip of the hat to Godot‘s blissful pre-occupation with time and how it is spent, or sometimes not spent. Byrne’s mantra, “Same as it ever was” (Byrne) seems a passive and careless acceptance of the life given. The emptiness of life itself and the filling of that space with anything. “Time isn’t holding us, time isn’t after us” (Byrne) leads the listener to believe that time is completely inconsequential to this existential crisis before leaving the character in question to stew in his crisis, “My god, what have I done?” (Byrne). His performance of the song likewise compliments the confusion. His movements consist of uncontrollable spasms, fidgety jerks and fluttering hand gestures. Byrne is never still and by the song’s end he is desperate to the point of lost diction. The chiaroscuro technique shrouds whatever kind of figure he is into half shadow before crossfading to a number of profile lanterns by the song’s finish give his performance almost a sense of catharsis.

Considering the strong thematic connection which the song holds in relation to Waiting for Godot, it is easy to see the influence and striking parallels between the two. Characters in both the song and the play are stuck in a spot from the perspective of both time and space no character can remember how they got to this moment in time and are blissfully ignorant of what is happening in the present. Byrne’s character at least still possesses enough humanity to experience a breakdown of sorts unlike Didi and Gogo who are so blissfully broken inside that suicide plays like a game for them that they always lose. They are even failures at death. They are so terribly unaware of how the world around them works that they cannot even die without causing an adverse effect. Nor will Beckett allow them to die. They are stuck and just as Byrne’s figure is just now discovering, they cannot leave the endless repetition of life, “We’re waiting for Godot” (Beckett, Godot 14). “Once In a Lifetime” uses that same lyrical repetition throughout the song’s passage , “You may ask yourself…” and “You may tell yourself…” (Byrne) to stress the character’s scepticism. Where Didi and Gogo can repress their hopelessness, Byrne’s character has to suffer through this crisis in the same state of total confusion, isolation and loss. “My god, what have I done?” (Byrne).

Work Cited

Antonio Silva, “David Byrne Interview.” Online video clip. Youtube. Youtube. 17 February 2007. Web. 29 February 2016.

Beckett, Samuel. Endgame. London: Faber and Faber, 2009. 5. Print.

—. Waiting for Godot. London: Faber and Faber, 1965. 5. Print.

Byrne, David. “Once In a Lifetime”. Talking Heads. Brian Eno, 1980. CD. From the album Remain in Light (1980).

Stop Making Sense. Dir. Jonathan Demme. Perf. David Byrne, Jerry Harrison. Cinecom. 1984. DVD.