In one of our earliest research seminars (EN6009), we were told part of our assignment required that we start a blog. The blog in question was described to us as “an informal way of expressing our academic interests” and a way of overarching those interests outside of college with what we are constantly learning. I like to think of it as a football bouncing off and between two parallel walls. The only question, “Where do I begin?”?

“With this blog, I aim to explore the relevance of what I learn in my MA to my own personal interests in Film and Literature. I am looking forward to the year ahead the challenges, the outcomes, the surprises and the rewards both academic and personal. Whatever lies on the road ahead.”

My first post was a simple “About” section. Looking back at it, I haven’t changed all that much. Still a cinema nut, still love making and watching movies, but now I feel with my MA, it has meant more to me now then it did then. I feel like as this blog has grown, I must admit, I was not wrong in predicting what lay ahead in the year.

At first I found it difficult to really explore this blog. Perhaps due to my lack of fluency in how to operate WordPress. Personally, I am not a fan of my early work on this blog. My Gone Girl article was my first attempt to fuse something I picked up in our feminism literature classes with texts which I personally enjoyed reading and watching. It is a nice reminded of how I tried at the start and a good comparison to now. As time went on, I found the seminar series held at UCC imperative to how I wanted to compose this blog. I took a lot of influence from how lecturers found their area of interest, invested in texts which both related and (seemingly) unrelated to the topic and asked questions. something I learned to embrace as this blog went on. Asking myself why I was writing and why I wanted an answer to begin with. I am particularly proud of my work on Dr. Tom Birkett’s The World Tree Project seminar, Hillary Lennon’s lecture on “The Irish Literary Letter” and later in January, Dr. Eibhear Walsh’s exploration of Elizabeth Bowen .

“The most notable part of the World-Tree Project and impassioned part of Dr. Birkett’s presentation was the question of the future and developing upon the progress already made by the program. Leaving with us with the question, what are the most effectives ways of translating and exhibiting resources from the Viking age? To me, this called into question, not just Viking age, but the technical age in general is diversifying as a whole and how online forums, encyclopedic sites and even search engines can and likely will change and improve by the same rationale as the World-Tree Project.”

The subjects of these seminars are all topics which I do not have any vested interest, but which as a result made me think harder about the argument that could be made from my standpoint. Being an outsider to the topics, I myself felt an advantage in conveying my own point of view.

“Lennon’s argument constantly came back to a matter of change and the chameleon like quality the letter takes as a source of literary and historical work as well as its future. Touching upon the technological innovations beyond formal authorial changes. The question becomes, is it still letter writing or are we now just lamenting the lost art form of which Boland wrote about or has the concept of letter writing transcended pen and paper to become a symbol or an ideal which is no longer bound by form? The world today can communicate just fine, but the real question remains to be seen, can the technological form still convey the beauty of written word? “

“But the presentation spoke of something louder, how does a pained and fragile writer like Bowen react when many in her position would simply become manifested by the repression they live through. Walshe mentioned A Time in Rome as a perfect example of Bowen’s trauma as a widow struggling while living in Cork, Ireland. Dr. Walshe answered simply, “identity”. Bowen’s Rome is her own interpretation, a singular expression of a place in time played through a sombre mood of mourning. Surely Bowen’s interpretation of the bust she sees in particular divides the landscapes of Rome as welcoming her femininity and Ireland as repressing her without console following her loss.”

I think it is important to mention my article on the movie Safe which marks a shift in direction towards the more refined and objective articles I am currently and have been writing of late. The objective of Safe Are you allergic to the 20th century” was to give a brief, theory supported by a mini argument and yet make it not only academic, but interesting to readers who may be familiar with the movie.

By the time January rolled around, I realised it was time to finalize my thesis topic. I knew I wanted to do something on cinema but still relate to the aspects of late Modernism and Postmodernism. By chance over the Christmas break I had watched a considerable number of Charlie Kaufman movies and the originality really ingrained itself in my head. Thinking for days about how these strands related to things on my course that I knew I would be studying soon. As it turned out Charlie Kaufman’s work really intrigued and gave me a heads up with what was to come.Then came the idea of my thesis, I wanted to start making this blog even more relevant to my overall thesis objective. I wanted to use this space to convey my growing familiarity with the different concept I picked up, discoveries I made and things which riveted me. I did not want my primary focus, the works of Charlie Kaufman, to become the central nucleus of everything I wrote. That seemed boring. So instead I opted to use this space to discuss the learnings I felt were relevant to the Charlie Kaufman thesis, but convey them through other relevant texts I found elsewhere, thereby challenging my own perspective beyond simply Kaufman and thinking more critically of how the learnings were used to create something individual in different ways.

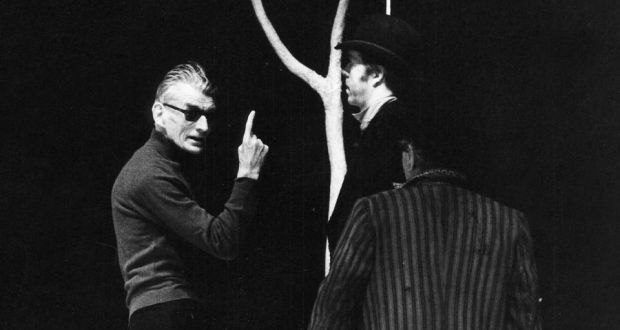

Samuel Beckett seminar seemed perfectly timed, Beckett’s relevance to Kaufman was something I picked up on and I am myself an avid fan of Samuel Beckett’s work. The blog article took quite a while to compose fully as I wanted to do justice to Beckett and the people who hosted said seminar.

“The shift of character’s thoughts (something which is also prevalent in Endgame) is immediately contradicted by life’s own refusal to give these characters a coda, “We’re waiting for Godot.” (Beckett, Godot 14) there’s no end to the record spinning on the turn table. Didi and Gogo are living life through the moving staves with frequent rests or (silences). How there was no one kind of music, the same way there is no one way of writing. This musicality comes through in his  stage directions which as Judy and Conor stressed were followed to the note. Beckett did not write to delineate from his original vision. Everything on page was there for to be followed. This amalgamation of lyrical musicality and to the note direction is perfectly illustrated in Endgame’s use of the [pause]. From this example alone, it’s clear to see Beckett’s musicality blends the forms, it’s drama, but there are clear elements of a lyrical verse style and the narrative prose at work too.

stage directions which as Judy and Conor stressed were followed to the note. Beckett did not write to delineate from his original vision. Everything on page was there for to be followed. This amalgamation of lyrical musicality and to the note direction is perfectly illustrated in Endgame’s use of the [pause]. From this example alone, it’s clear to see Beckett’s musicality blends the forms, it’s drama, but there are clear elements of a lyrical verse style and the narrative prose at work too.

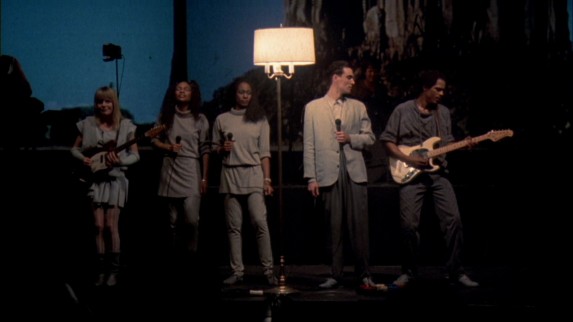

Even after the Beckett seminar article, I felt there was more to say and conceptually I had a text which I felt paralleled with Beckett’s approach to the stage. Having the opportunity to discuss how a Talking Heads concert relates to the staging of Samuel Beckett made me slightly giddy. I was taken aback by the liberty of getting to discuss something this interesting and still relate it to my academic work for the first time in my college experience. I think at this point in my blog, I was really starting to embrace my own voice and realised just how cathartic this blog could be and how foolish I was for not seeing the endless potential which WordPress allowed between personal interest and academic study.

“I am to understand that the intent of Beckett’s work is to evoke, subvert and question the mimetic medium of the stage which is why I wonder if perhaps Stop Making Sense is, in it own way, trying to do something similar through a rock concert. Much like a theatre play, Stop Making Sense relies heavily upon stage lighting, blocking, exaggerated performance and movements as well as a narrative sequence of unfolding shifts and changes in the band’s dynamic. There are props (most notably a lamp and a pair of reading glasses) and even subtle costume and hair style changes from Byrne. But the comparison to Becket, for me, is Byrne himself and his seemingly intentional decision to never leave the stage. A class troupe of Beckett’s drama and raison d’etre..”

The Editathon from back in February was particularly fun to write about. I edited Alex Garland’s Wikipedia page and did some research on his career and added further parts on to the post. This article change from the usual criticism and argument based work I was trying before. Thoroughly enjoyed the experience.

“I chose Alex Garland, writer and director of the recent science-fiction parable Ex Machina. Garland had only been nominated for an Academy Award two weeks prior and being a fan, I saw his page as a golden opportunity to improve with any new information I could collect. I took the week before our test to re-familiarise myself with Wikipedia’s layout and conceptually drew upon other pages I was studying (particularly director Danny Boyle and actor Michael Fassbender, both of which have very simple, but detailed Wikipedia pages). I composed the formats for three new tables, assigning the new headings for Films, Novels and Video Games. I began the session that morning with implementing said tables which would become the centre-pieces (as I saw them) of the newly revamped page. What I had not anticipated were the potential errors with correct data coding. However, with Donna’s expertises and the help of the Wikipedia message message board discussion, problem solved!”

The blog article for the mini-conference was a joy to write. It was a little more informal and more narrative based than I had planned, but it really does reflect how emotional the day became.

The blog article for the mini-conference was a joy to write. It was a little more informal and more narrative based than I had planned, but it really does reflect how emotional the day became.

“Looking at the photos I had taken and the tweets I had written and even remembering the taste of the coffee and croissant I had during break-time, there’s an undeniable sentimentality attached to it all. The mini-conference to me was not a personal triumph, it was a team effort built upon mutual support and friendship as well as the incomparable efforts of our co-ordinators and lecturers. It’s been two weeks since I entered the Western Gateway Building in fearful anticipation, but I know it’s a day that I will remember, unconsciously exaggerate, maybe even recollect on occasion in years down the road, but never forget.”

My Formless Form article came about as a result of a discussion I had with UCC lecturer Dr. Lee Jenkins. When asked if we could think of any later examples of responses to T.S Eliots’ “The Waste Land”. I thought of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue Album. I argued by explaining how, I personally found his use of improvisation during a period of what I saw to be declining Modernism. I felt Van Morrison was lyrically comparable to Davis and I even brought in one of my favourite artists, Joseph Turner.

Both album and poem also subvert conventional form, “The Waste Land” for example alternates from verses of free form run on lines with minimal punctuation to a clear mimetic verse style of romantic origin. Lines 77-93 of “A Game Of Chess” is a perfect example of this literary improvisational style equivalent to what Davis illustrates musically throughout Kind of Blue. Davis’ punctuation amounts to staccato phrasing and musical rest. “Freddie Freeloader” illustrates this kind of controlled improvisational style beautifully in a major key. Most striking of this improvisation and Davis’ phrasing are his use of the imperfect cadence at the end of each piece which seems to string together every song. “The Waste Land”, similarly, never feels like a finished piece of work, but still feels connected not only through its repetition, but its motifs of language, onomatopoeia and exclamation.

Both album and poem also subvert conventional form, “The Waste Land” for example alternates from verses of free form run on lines with minimal punctuation to a clear mimetic verse style of romantic origin. Lines 77-93 of “A Game Of Chess” is a perfect example of this literary improvisational style equivalent to what Davis illustrates musically throughout Kind of Blue. Davis’ punctuation amounts to staccato phrasing and musical rest. “Freddie Freeloader” illustrates this kind of controlled improvisational style beautifully in a major key. Most striking of this improvisation and Davis’ phrasing are his use of the imperfect cadence at the end of each piece which seems to string together every song. “The Waste Land”, similarly, never feels like a finished piece of work, but still feels connected not only through its repetition, but its motifs of language, onomatopoeia and exclamation.

“Unlike Davis, Morrison embraces form within musical structure but uses this form to lyrically build a narrative around a conscious, introverted character (usually the clichéd lover and the scepticism of romance) like a novel. In this way, the listener gets an ulterior monologue or soliloquy akin to say William Faulkner. He similarly makes use of repetition, realism and impressionistic word painting, at times, even abstract details through first person narration. Morrison also breaks meter, rhyme becomes a tangent of vocal improvisation or digressions of thought in the form of more repetition. Take the lyrics to “Astral Weeks” for example, Morrison like painter Joseph Turner an impressionistic picture from a distance. “If I ventured in the slipstream, Between the viaducts of your dream, Where immobile steel rims crack, And the ditch in the back roads stop, Could you find me?” (Morrison) Much like Turner’s art, Morrison’s music recounts a specific moment in time. He shades his vision with interrogation or a subjective eye for the details he recounts and his uses interrogative language which disrupts the music and the seeming blissfulness of what he describes.“

Then the idea of “Lynchian” really popped out to me as an area of interest for a blog post. As an avid David Lynch fan it also gave me the opportunity to reread Breton’s “Manifesto of Surrealism”. I thoroughly enjoyed the research for this particular article and I found a lot Lynch’s influence was applicable to, if not directly inspiring to Kaufman. The article also gave me the chance to revisit Freud’s “The Uncanny” which I subsequently used for my final blog post on The Shining.

“Where surrealism bases itself entirely upon avoiding the mundane, the “Lynchian” manifests surrealism through the mundane and this is where Foster-Wallace’s key word, “containment” becomes an epitome of how we understand “Lynchian-surrealism”, a form of surrealism which is inexplicably embedded in our reality, a contradiction of the manifesto of surrealism yet still perfectly fit to fashion Lynch’s vision. Where surrealism is traditionally manifested internally through the unconscious projection in the way of dreams, hallucinations, Lynchianism transplants it to the external of unflinching reality. In this way, Lynch traps the imagination in a sort of misplaced morality and an obsessive compulsive mystery In short, Lynch creates an exaggerated reality of living through surrealism but balances just enough realistic structure to make the viewer comprehend on an unconscious level. It allows Lynch to accelerate the narrative yet provide intrigue.”

The article I wrote on Nietzsche’s influence over David Bowie’s early work was much more of a tribute to a great musician. Beyond music, Bowie showed how relevant literature was to music and he himself embodied that special kind of individual who didn’t fear mixing the two and making the result completely his own. I had read Thus Spoke Zarathustra before engaging in the idea for the article and I am very proud of the connections and work I did.

“So what is Bowie’s real argument on this album? Well “Life on Mars” asks the most relevant question, “Is there life on mars?” why do we not know anything outside of ourselves and why is the world at present moving in a perpetual loop to appease some misplaced fear of the future? These song’s satirical commentary of lost innocence as a result of this mentality takes on a poignant irony. And this is where Nietzsche’s revaluation of value comes to light. Where The Man Who Sold The World was preoccupied with illustrating the fault of democracy and power of religion, it also showed a fear for the value individuality. In a song like “All The Madmen” and the lyric ” Day after day, They take some brain away, Then turn my face around, To the far side of town, And tell me that it’s real. Then ask me how I feel.” (Bowie)”

Truth be told, with such a limited time left before deadline of this blog, I felt the most relevant post I wanted to make was on Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining and it’s portrayal of Freud’s “The Uncanny”. It was a good opportunity to investigate those parallels I had often heard critics talk about and as The Shining is a relevant text on my MA course, I felt it was a good opportunity to begin research into anything which might pop into the Charlie Kaufman thesis considering “The Uncanny” is a shared source of influence on both.

“It’s interesting that Jack’s uncanny meetings mirror (and I mean mirror both metaphorically and literally) his struggles and repression. His alcoholism is foiled by the bartender who encourages his boisterous behaviour, his sexual desires are teased by the figure in room 237 and his spells of violent anger and discontentment towards his family are mirrored by the projection of the murderous caretaker who encourages he murder them.”

Then finally, there was a special post about the man himself, Charlie Kaufman.

“I would like to look at Kaufman’s approach to narrative structure and his decisions to parallel and even bridge between the internal consciousness and how he portrays an almost uncanny external unconscious consumer-driven world which his characters are in turn shaped. This will tie in with chapter two’s behavioural study of key characters and again reinforce the idea of identity stemming on a practical level from their worlds as well as Kaufman’s approach to postmodernism. For this chapter I believe Lyotard’s work on the foundations of postmodernism are imperative reading for the understanding of Kaufman’s layered characterizations. Lyotard’s book, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge which relates the shifting paradigm of the world (and in a sense, the human condition) with cultural change and assimilation. I believe the theories outline by Lyotard play a major influence on Kaufman’s use of satire, parody and pastiche as means of illustrating identity as another changing paradigm. Jameson’s approach to consumer society will also feature in this chapter. his work, Postmodernism or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism and his essay, “Postmodernism and the Consumer Society” will be integral in expanding upon Lyotard’s relevance to Kaufman’s world.”

Twenty-two posts, eight months and one budding scholar later I feel this blog has set my imagination alight. Is it a perfectly crafted work of ingenious and nuanced critical thinking, not at all, but I wouldn’t want it to be. It’s a reflection of personality, it is a mirror to my interests and myself and regardless of the academic outcome, I will continue adding to this blog after this assignment ends.

Work Cited

Beckett, Samuel. Waiting for Godot. London: Faber and Faber, 1965. Print.

Bowie, David. “All The Madmen”. David Bowie. Tony Visconti. 1970. CD. From the album The Man Who Sold the World (1970).

“Life on Mars”. David Bowie. Ken Scott. 1971. CD. From the album Hunky Dory (1971).

Curran, Martin. “Introduction: This Must Be The Place.” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 22 September 2015. 1 April 2016. Web.

—. “Seminar Series: From Viking Ships to Reading Lists: Connecting Cultures with the World-Tree Project.” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 22 November 2015. 1 April 2016. Web.

—. “Seminar Series: Irish Literary Letters: Art & Argument” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 7 December 2015. 2 April 2016. Web.

—. “Seminar Series: Samuel Beckett: From Words on a Page to Actors on a Stage” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 16 January 2016. 1 April 2016. Web.

—. “Seminar Series: Elizabeth Bowen and the Landscape of Loss” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Loverand Masters Student . WordPress. 30 January 2016. 1 April 2016. Web.

—. “From Samuel Beckett to The Talking Heads: Performance Art & The Theatre of the Absurd”” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 10 February 2016. 3 April 2016. Web.

—. “The First Annual UCC Editathon!” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 29 February 2016. 3 April 2016. Web.

—. “Malkovich, Malkovich, Malkovich: A Reflection” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 13 March 2016. 3 April 2016. Web.

—. “Formless Form: “Literary and Cultural Modernism as Musical Interpretation” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 22 March 2016. 3 April 2016. Web.

—. “What is “Lynchian”?: The Auteur, The Fashionably Surreal and The Avant Garde” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 30 March 2016. 3 April 2016. Web.

—. “From Zarathustra to Ziggy: Nietzsche’s Influence on David Bowie ” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 1 April 2016. 3 April 2016. Web.

—. “All Work and No Play Make Sigmund a Dull Boy: Freud’s The Uncanny and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 3 April 2016. 3 April 2016. Web.

—. “The Works of Charlie Kaufman: An IT and Literature Review” Web log post. Marty288: Cinema Fanatic, Literature Lover and Masters Student. WordPress. 4 April 2016. 4 April 2016. Web.